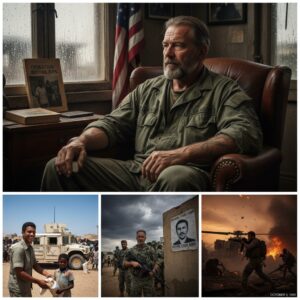

I still remember the smell of Mogadishu. It wasn’t just the heat or the ocean; it was the smell of burning tires and something old, something crumbling.

It’s been over 30 years, but I can close my eyes and be right back there. October 1993. Most people know the movie, but the movie is just noise. The reality was quieter at first, and then it was loud enough to break you.

We arrived with good intentions. You have to understand that. Back in late ’92, when the Marines first hit the beach, we were there for “Operation Restore Hope.” We were handing out rice to starving kids. The country had been ripped apart by drought and warlords fighting for scraps after the government collapsed. We were the good guys. We were the shield.

But by the summer of ’93, the atmosphere had shifted. The humanitarian mission bled into something else. We weren’t just feeding people anymore; we were hunting a ghost. General Mohamed Farrah Aidid. He’d been a general under the old dictator, Barre, and now he wanted the throne. He was starving his own people to get it, hijacking the very food we were bringing in.

The UN tried to play politics, but Aidid played war. He ambushed 24 Pakistani peacekeepers in June, butchering them. That changed everything for us. The rules of engagement got muddy. We were fighting with one hand tied behind our back, trying to capture a warlord in a city where every window could hide a gunman.

On the afternoon of October 3rd, the call came down. We got intel that two of Aidid’s top lieutenants were meeting at a place near the Olympic Hotel, right in the heart of the Bakara Market. That was Aidid’s stronghold. “The Black Sea,” we called it. hostile territory.

It was a Sunday. We were relaxed, writing letters home, cleaning gear. Then the sirens went off. “Irene. Irene.”

We geared up. The plan was simple: In and out. A daylight raid. Fast rope down, grab the targets, load them into the convoy, and drive back to base. Estimated time: 30 minutes.

I looked at the guy next to me in the bird. He was just a kid, really. We all were. We had no idea that the city below us was waking up, and it was angry. We had no idea that the assumptions we made—that our tech and our speed would save us—were about to collide with a reality we weren’t ready for.

As we lifted off, the dust swirled around the Black Hawks. I felt a knot in my stomach. Not fear, exactly. Just a heaviness. Like the air pressure had dropped.

We were flying into a hornets’ nest, and we were about to kick it wide open.

Part 2: The Hornet’s Nest

The first thing you lose isn’t your nerve; it’s your senses. Or rather, they get overwhelmed to the point where they stop functioning like they do in the normal world.

We were flying low over the Indian Ocean, banking hard toward the coastline. The water was a brilliant, indifferent blue, crashing against the white sand. It looked like a postcard, like a vacation spot, until you saw the smoke rising from the city beyond the dunes. Mogadishu wasn’t a city anymore; it was a skeleton. A maze of concrete scarred by years of civil war, clan fighting, and neglect.

I was in the back of a Black Hawk, legs dangling off the side. The wind was whipping my face, grit stinging my eyes even behind the goggles. We were part of Task Force Ranger. Our job was supposed to be surgical. The plan was terrifyingly simple on paper: Assault force hits the target building near the Olympic Hotel, secures the “precious cargo”—two of Mohamed Farrah Aidid’s top lieutenants—and then we extract.

“Thirty minutes,” the briefing officer had said. “In and out. Don’t get comfortable.”

As we crossed the transition point from the ocean to the city, the landscape changed instantly. The tin roofs of the shanties reflected the harsh afternoon sun like a sea of broken mirrors. Below us, I could see people. Not just a few, but hundreds. Thousands. They stopped what they were doing and looked up. Then, they started running. And they weren’t running away from us; they were running toward where we were going.

The tires were already burning. That was their signal. Black smoke columns rose up like signal fires, marking our path for every gunman with an AK-47 in the city. The element of surprise? We lost that the moment the rotors started turning back at the airfield.

“One minute!” the crew chief screamed over the headset.

My stomach did that familiar flip—the mix of adrenaline and the primal fear of leaving a perfectly good aircraft to drop into a hostile zone. We were heading for the Bakara Market. This wasn’t just enemy territory; this was the heart of darkness. It was Aidid’s backyard, his stronghold. The Intelligence guys called it the “Black Sea” because if you went in, you didn’t come out.

The bird flared, the nose pitching up aggressively to bleed off speed. The G-force pressed me down, heavy and suffocating. Then came the dust.

We call it a “brownout.” In Somalia, the dirt isn’t just dirt; it’s this fine, powdery filth that hangs in the air. As the Black Hawk hovered, the rotor wash kicked up a blinding cloud of red-brown earth, trash, and debris. The world outside the helicopter vanished. I couldn’t see the ground. I couldn’t see the buildings. I could only see the swirling chaos.

“Ropes! Ropes! Go! Go! Go!”

I grabbed the thick braided rope. You don’t slide down a fast rope; you fall in a controlled manner, squeezing with your gloves and boots to keep from breaking your legs when you hit. But in the brownout, you have no depth perception. You don’t know if the drop is twenty feet or fifty.

I threw myself out. The heat hit me first—a physical wall of humidity and rot. Then the friction burn through my heavy leather gloves. I slid down into the opaque cloud, waiting for the impact.

Thud.

My boots hit the hard-packed dirt. I rolled, bringing my weapon up, my heart hammering against my ribs like a trapped bird. The dust was choking. I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. I blinked, trying to clear the grit, and as the dust began to settle, the sound hit me.

It started as a pop. Just a single pop. Then another. And then, the air ripped open.

Snap-crack. Snap-crack.

Bullets passing supersonic close to your head make a distinct sound. It’s not the bang of the gun; it’s the snap of the air breaking. And the air was snapping everywhere.

We had landed right in the middle of it. The market was waking up, and it was angry.

I sprinted to a pile of rubble—what used to be a wall—and took a knee, scanning my sector. The assault team, the Delta operators, were already moving on the target building. They were the scalpel; we, the Rangers, were the sledgehammer. We were the perimeter, the four corners set up to keep the bad guys out while Delta did their work inside.

“Chalk Four, set!” I yelled into my comms, though I could barely hear myself.

The streets of Mogadishu were narrow, alleyways twisting like a labyrinth. And from every alley, they came. Skinny men in tattered shirts, some high on Khat—the local stimulant that made them fearless and numb—spray-and-praying with AK-47s. They didn’t aim; they just pointed the metal down the street and held the trigger.

But it wasn’t just the militia. It was women pointing out our positions. It was kids running ammunition. The whole city was weaponized against us.

“Contact front!” someone screamed.

I saw muzzle flashes from a window across the street. I raised my rifle, squeezed off a controlled burst. The window shattered. The shooting stopped for a second, then started again from the roof.

Despite the chaos outside, the radio chatter from the assault team was calm, almost professional. They had breached the Olympic Hotel meeting site. They had the targets.

“Jackpot. We have the HVTs (High Value Targets). Preparing for extraction.”

I checked my watch. It had been maybe twenty minutes. We had done it. We had kicked the door in, grabbed Aidid’s lieutenants, and we were getting ready to load them onto the convoy of trucks and Humvees that had ground its way to our position.

I allowed myself a split second of relief. We’re going home, I thought. Just load the trucks, drive back to base, grab a cold water.

That was the mistake. You never relax. Not in the Mog.

The convoy pulled up, a line of heavy trucks and Humvees. The Delta guys were hustling the prisoners out, heads bagged, zip-tied. It looked sloppy, but it was working. We were collapsing the perimeter, getting ready to mount up. The volume of fire was increasing—RPGs were starting to streak across the sky like angry comets—but we were leaving.

Then, at 16:20 hours, the world changed.

I heard a sound that I will never forget as long as I live. It wasn’t a gunshot. It was a whoosh, followed by a hollow, metallic impact.

I looked up. High above the market, Super 61—Cliff Wolcott’s Black Hawk—was holding a steady orbit, providing sniper cover for us. He was our guardian angel.

The RPG hit the tail rotor. It didn’t look like a movie explosion. It was mechanical, brutal. The tail rotor just… disintegrated.

For a second, the massive helicopter hung in the air, suspended in time. Then, the physics took over. Without the tail rotor to counter the torque of the main blades, the machine began to spin. Slowly at first, then violently.

“Hit! hit! 61 is going down!”

The radio net exploded. The calm voices were gone, replaced by urgent, piercing shouts.

I watched, frozen, as the helicopter gyrated wildly, smoke pouring from the tail. It fell out of the sky, dipping below the roofline of the city.

CRASH.

The sound of five tons of metal hitting the earth echoed through the streets, shaking the ground beneath my boots. A plume of black smoke rose up from the crash site, marking the spot.

“Super 61 is down. Super 61 is down.”

The silence that followed in my head was louder than the gunfire.

In that instant, the mission profile shattered. We weren’t capturing warlords anymore. We weren’t leaving. The “in and out” raid was dead. The prisoners didn’t matter. The politics didn’t matter.

We had men down. Cliff Wolcott. Donovan Briley. The crew in the back. They were somewhere in that maze, surrounded by thousands of armed militia who were converging on the smoke like sharks to blood.

We don’t leave people behind. It’s the religion of the Ranger. It’s the only thing that matters.

“New orders!” The voice of the platoon sergeant cut through the daze. “We are moving to the crash site. We are securing the bird. Let’s move!”

The plan dissolved into improvisation. The convoy, which was loaded with the prisoners, now had to fight its way through the narrowest, most dangerous streets in the city to get to the crash. And we, the Rangers on the ground who hadn’t loaded up yet, had to move on foot.

I stood up, my legs feeling heavy, my mouth dry as dust. The 30-minute timer in my head was gone. I checked my ammo. I had entered the fight with a standard load, thinking it would be plenty. Now, looking at the swarm of militia pouring out of the woodwork, I felt naked.

We started moving toward the smoke.

The city of Mogadishu, which had been a hostile environment, now transformed into a slaughterhouse. As we moved down the alleyways, the intensity of the fire doubled, then tripled. They were on the rooftops, in the windows, behind cars.

RPGs weren’t just for helicopters anymore. They were skipping them off the ground at us, firing them down alleyways. The explosions were deafening, the concussions rattling our teeth.

“Keep moving! Keep moving!”

We bounded from cover to cover. A doorway. A rusted car. A pile of trash. Every intersection was a death trap. We’d cross, bullets kicking up dirt at our heels, and return fire, suppressing the shadowy figures in the windows.

I saw a Somali gunman step out from behind a corner, raising his AK. I dropped him. Two more stepped over his body without hesitating. They didn’t care. They just kept coming. It felt like we were fighting the tide.

Meanwhile, the convoy was getting hammered. Over the radio, I could hear the drivers screaming. They were taking heavy fire. Windshields were shattering. Gunners in the turrets were getting hit. They were navigating a gauntlet, trying to turn heavy trucks around in streets meant for donkey carts, all while taking fire from 360 degrees.

“I need a medic! I need a medic here!” The calls for help started to bleed into the command net.

We were taking casualties. Good men. Friends.

But the focus remained on that column of black smoke rising in the distance. Super 61. Wolcott. We had to get there.

As we fought our way closer, the reality of the situation settled in. This wasn’t a skirmish. This wasn’t a raid. This was a full-scale war in a space the size of a few city blocks. We were cut off, we were outnumbered, and the sun was starting to dip lower in the sky.

Then, the unthinkable happened again.

The radio crackled with a voice that sounded strained, desperate.

“Super 64 is going in. I repeat, Super 64 has been hit.”

My heart stopped. Not another one. Please God, not another one.

Mike Durant’s bird. Super 64. He had been circling, trying to cover us, trying to keep the mob off our backs. And they had got him too.

I looked up to see a second Black Hawk trailing smoke, wobbling, fighting to stay in the air. It drifted away from us, over the sprawling slums, deeper into enemy territory.

It crashed about a mile away from the first site.

Now we had two crash sites. Two crews down. The city was split in half. The force was split in half. And the enemy was everywhere.

The sun was setting, casting long, blood-red shadows across the killing zones. We were trapped in Mogadishu. The hornet’s nest wasn’t just stirred up; we were inside it, and we were being stung to death.

I gripped my rifle tighter, my knuckles white. The objective was no longer about winning. It was about survival.

End of Part 2

Part 3: The Alamo in the City

The sun in Mogadishu doesn’t set like it does back home. In Georgia, twilight lingers; it gives you a moment to breathe, to adjust. In the Horn of Africa, the sun drops like a stone. One minute you’re sweating in the blinding white heat, and the next, the shadows are stretching out like long, black fingers, grasping at everything in the streets.

But before the darkness took us completely, we had to watch the hope die.

We were fighting for inches near the first crash site—Super 61, Cliff Wolcott’s bird. We had set up a perimeter in a cluster of buildings made of crumbling concrete and corrugated tin. We were taking fire from three sides. The air was thick with the smell of burning rubber, cordite, and that specific, copper tang of blood that you taste in the back of your throat when the adrenaline dumps into your system.

We thought we had it bad. We thought we were in the worst spot on Earth. Then the radio crackled, and we realized there was a level of hell below ours.

“Super 64 is down. I repeat, Super 64 is down.”

I froze. I was changing a magazine, my hands slick with sweat and grime, and I just froze. Mike Durant’s bird. He was the one orbiting, keeping the skinnies—the militia—off our backs. And now he was gone.

He had crashed about a mile away, deep in the maze of the city, in an area we had zero control over. It was a chaotic, hostile sector, swarming with Aidid’s militia. And we were stuck. We couldn’t get to him. The ground convoy was being chewed up in the streets, taking RPG hits and heavy machine-gun fire, unable to break through the roadblocks to reach us, let alone get to Durant.

We were the trapped. And now, Durant and his crew were the abandoned.

The radio traffic that followed is something that haunts me every single night. It wasn’t panicked. That’s the thing about the operators—Delta Force. They don’t panic. They get quieter. They get more precise.

We heard the call come in from Super 62, the Black Hawk providing cover over Durant’s crash site. Two snipers, Master Sergeant Gary Gordon and Sergeant First Class Randy Shughart, were on board. They were looking down at the wreck of Super 64.

They could see the movement in the streets. The mob was surging toward the crash site like a colony of ants swarming a piece of dropped candy. Hundreds of them. Armed with AK-47s, rocks, machetes. And down there, in the twisted metal, Durant and his crew—Ray Frank, Tom Field, Bill Cleveland—were alive but badly hurt. They were sitting ducks.

I heard the request over the net.

“Request permission to insert.”

It was a calm voice. A professional voice. Gordon and Shughart were asking to be put on the ground.

The command came back: “Negative. Stay in the air. We’re working on a relief column.”

The commanders knew. They knew what was down there. Putting two men on the ground against hundreds wasn’t a tactical maneuver; it was a death sentence.

But the mob was getting closer. We could hear the volume of fire increasing from that direction.

“Request permission to insert.”

They asked again. They weren’t asking to win the battle. They weren’t asking to save the day. They were asking for permission to go down there and die so that their brothers wouldn’t have to die alone.

There was a pause. A long, agonizing static hiss.

“Go.”

I didn’t see it happen with my own eyes—I was too busy trying to keep my head attached to my shoulders at the first crash site—but we all felt it. We knew what was happening. We pictured it. The Little Bird touching down in the dust. Two men jumping out. Two men running toward the fight.

Gordon and Shughart fought their way to the crash. They pulled Durant and the others from the wreckage. They established a perimeter. Two men. Just two.

For twenty minutes, they held back the entire city.

Think about that. Twenty minutes in a gunfight is an eternity. A gunfight usually lasts seconds. You shoot, you move, it’s over. But for twenty minutes, those two Delta operators stood their ground. They were calm, precise executioners. They picked their targets. They conserved their ammo. They moved around the helicopter, creating the illusion that there were more of them than there actually were.

Reports later said they killed at least 25 militia members and wounded dozens more. They stacked the bodies of the enemy like sandbags. But math doesn’t work in a fight like that. For every one they dropped, three more came around the corner.

We listened to the radio as the situation deteriorated. We heard the calls for ammo. We heard the urgency creep in, not out of fear, but out of necessity.

Then, the silence.

Gordon fell first. He had gone around the other side of the bird to flank the enemy, and he didn’t come back. Shughart picked up Gordon’s weapon—a CAR-15—and gave it to Durant. He said something brief, something simple. “Good luck.” And then he went back to the fight.

He fought until his rifle ran dry, until he had nothing left but his sidearm. And then he fought with that.

When the radio from that sector went dead, a coldness settled over us at the first crash site. We knew. We didn’t say it, but we knew. They were gone. Gordon. Shughart. The crew—Frank, Field, Cleveland. All dead.

And Durant? We didn’t know then that he had survived the mob, that he was being dragged away to be held prisoner for 11 days. We just assumed the worst. We assumed they were all gone.

That knowledge changed us. It hardened us. The mission was no longer about politics or warlords or UN resolutions. It was about rage. It was about grief. It was about making sure that if we were going to die in this godforsaken city, we were going to take as many of them with us as we could.

Back at our position—the “Alamo”—the sun had finally vanished.

Night in Mogadishu isn’t dark. It’s a strobe-light nightmare. The sky was filled with the green streaks of tracers. Our tracers were red; theirs were green. It looked like a deadly Christmas display.

We were pinned down in a courtyard and a few surrounding structures. We had the wounded in the center, in what we called the casualty collection point (CCP). It was a slaughterhouse.

The screams of the wounded were the worst part. You expect the noise of the guns. You expect the explosions. You don’t expect the sound of your friends—tough men, Rangers who would walk through fire without complaining—crying out for their mothers.

We had guys with gunshot wounds to the legs, the stomach, the chest. We were running out of IV fluids. We were running out of bandages. The medics were working miracles in the dirt, doing surgery by the light of chemlights, their hands covered in the blood of their friends.

“I need pressure here! Hold this!”

“He’s bleeding out! I can’t stop it!”

I was at a window, staring out into the blackness through my Night Vision Goggles (NVGs). The world turned green and grainy. The NVGs gave us an edge. The Somalis didn’t have them. We could see them moving in the shadows, setting up ambushes, creeping toward our walls.

“Movement, eleven o’clock. Alleyway.”

I raised my rifle. The laser designator on my barrel painted a dot on the chest of a man carrying an RPG. I squeezed the trigger. The man dropped.

But they kept coming. It was like fighting water. You push it back, and it just flows around you. They were on the rooftops, shooting down into our courtyard. They were firing RPGs into the walls, showering us with concrete dust and shrapnel.

The psychological weight of the situation began to crush us. We were the best military in the world. We had the best tech, the best training. And we were trapped in a third-world city, surrounded by guys in flip-flops chewing a narcotic leaf, and we were losing.

We felt cut off. The convoy—the “Lost Convoy”—had tried to reach us and failed. They had taken so many casualties they had to turn back to base. We listened to their screams on the radio, too. We knew they weren’t coming.

We were on our own.

“Ammo check!”

“I’ve got one mag left!”

“I’m out of frags!”

“Share what you have. Make every shot count.”

That was the order. Make every shot count. We stopped firing full auto. We stopped suppressing fire. We only shot when we had a target. We were hoarding bullets like they were gold coins.

I looked around the room during a lull in the fighting. The faces of the men around me were masks of exhaustion and grime. Eyes wide, pupils dilated. Some were praying. Some were just staring at the wall. But nobody was quitting.

That’s the thing about the “brotherhood” people talk about. It sounds like a cliché until you’re there. In that room, I didn’t care about the President. I didn’t care about the United States. I didn’t care about the mission. I cared about the guy to my left and the guy to my right. I fought because I didn’t want them to die. And they fought because they didn’t want me to die.

We were an organism, fighting for survival.

Then, the sky roared.

It started as a low buzz, like a swarm of angry bees, and grew into a deafening howl. The Little Birds. The AH-6 assault helicopters.

“Star 41, this is Barber 52. We are inbound for gun runs. Keep your heads down.”

I watched through the window as the Little Birds dove out of the black sky. They came in steep and fast.

BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRT.

The sound of the miniguns is not a gunfire sound. It’s a tearing sound. Like the sky is ripping open. A stream of red tracers poured from the helicopters like water from a firehose, saturating the rooftops and alleyways where the militia were massing.

The explosions were blinding. The Little Birds were flying so low we could feel the rotor wash. They were flying down the streets, below the rooflines, hunting.

“Yeah! Get some! Get some!”

For the first time in hours, a cheer went up from our position. It was a savage, primal cheer. The “Night Stalkers”—the pilots of the 160th SOAR—were the only reason we were still breathing. They stayed on station all night, refueling and rearming in minutes back at the airfield and coming right back. They were our lifeline.

But even with the air support, the situation on the ground was critical.

We had Corporal Jamie Smith. He had been shot in the leg. The bullet had severed his femoral artery. The medics were trying everything. They had packed the wound, they were applying pressure, but the bleeding wouldn’t stop.

“We need a medevac! Now!”

“Negative. Too hot. We can’t land a bird.”

That was the reality. We couldn’t get a helicopter in to pick him up because the RPG fire was too intense. We watched him fade. We watched the life drain out of a twenty-one-year-old kid because we couldn’t get him to a hospital three miles away.

He died there on the floor of that building, surrounded by his brothers who were powerless to save him.

That broke something in us. It took the fear away and replaced it with a cold, hard hatred. We stopped worrying about dying. We just wanted to kill everyone who was trying to kill us.

The hours dragged on. 0200. 0300. 0400.

The water ran out. Our mouths were so dry we couldn’t swallow. We were dehydrated, running on adrenaline and hate. The fighting would lull for ten minutes, and then explode again with ferocity.

I remember sitting against a wall, looking at a picture of my wife I kept in my helmet. It felt like looking at a photo from another century. That life—the barbecues, the grocery shopping, the traffic jams—felt like a dream. This, the dust and the blood and the noise, this was the only reality.

“They’re organizing,” the platoon sergeant said, peering into the darkness. “They’re going to hit us with everything they have before dawn.”

He was right. The Somalis knew that once the sun came up, we would get more air support. They knew their window was closing.

They launched a massive assault around 0430. RPGs slammed into the walls of our building, blowing holes in the masonry. Gunfire erupted from every direction. It was a wall of lead.

“Hold the line! Hold the line!”

We were firing our last magazines. I was picking up magazines from the wounded, wiping the blood off them, and loading them into my weapon.

We were the Alamo. We were surrounded. We were cut off. And we were ready to die right there.

But we weren’t going to die alone.

End of Part 3

Part 4: The Mogadishu Mile

We measured time in heartbeats and magazine changes. By the time the sky began to turn from that suffocating black to a bruised, purple grey, we had stopped checking our watches. The concept of “time” had ceased to exist. There was only “alive” and “dead,” and the margin between the two was getting thinner with every passing second.

We were still at the first crash site—Super 61, Cliff Wolcott’s bird. We had been fighting for over twelve hours. My canteen was dry. My lips were cracked and bleeding. The adrenaline that had sustained us through the night was gone, replaced by a leaden exhaustion that settled deep in the marrow of my bones. Every movement felt like wading through wet concrete.

But we couldn’t stop. To stop was to die.

The Somalis knew the sun was coming. They knew that daylight brought the Little Birds back in force. They knew their window to overrun us was closing. So, they threw everything they had at us in those pre-dawn hours. The volume of fire was a physical weight, pressing us into the dirt. RPGs skipped off the ground, detonating against the walls of our makeshift strongpoint. The air was so thick with dust and pulverized concrete that you had to chew it to breathe.

Then, we felt it before we heard it.

A vibration. A deep, rhythmic thrumming that shook the ground beneath our boots, distinct from the sharp cracks of the rifles and the booms of the grenades. It was a heavy, industrial sound.

“Armor,” someone whispered. “It’s the armor.”

Around 0700 hours on October 4th, the relief column finally punched through .

It wasn’t just a few Humvees this time. It was a monster. The United Nations had finally gotten its act together. We saw the silhouettes emerging from the smoke and the morning mist: Malaysian Condor APCs (Armored Personnel Carriers) and Pakistani M48 tanks . They looked like prehistoric beasts, grinding over the debris, their engines roaring a challenge to the city.

The sight of those tanks was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. They were ugly, loud, and painted in UN white, but to us, they looked like chariots of fire.

But the arrival of the column didn’t stop the fighting. If anything, it intensified it. The militia poured fire into the convoy. The tanks responded, their main guns booming, shaking the fillings in our teeth. The Malaysian APCs fired their heavy machine guns, sweeping the rooftops. It was a cacophony of violence that drowned out every thought.

“Get the wounded! Get the wounded out!”

The orders came down the line. We broke cover, dragging our injured brothers toward the APCs. The back doors of the white vehicles swung open, revealing the cramped, dark interiors. We shoved the stretchers in. We pushed the walking wounded inside.

It was chaos. The drivers didn’t speak English well. We were screaming, they were shouting in Malay and Urdu. But the language of urgency is universal.

“Go! Go! Go!”

We loaded the prisoners—the HVTs we had captured what felt like a lifetime ago—into the vehicles. It seemed absurd that we still had them. The mission had been to grab them, and we did, but the cost… the cost was astronomical.

Then came the hardest part. The part that took the longest.

We couldn’t leave Cliff.

We had recovered the body of his co-pilot, Donovan Briley, but Cliff Wolcott’s body was trapped in the wreckage of the Black Hawk. The nose of the aircraft had crushed in on impact. We weren’t leaving without him. Rangers don’t leave Rangers.

The rescue team brought out the saws. In the middle of a raging firefight, with bullets snapping overhead and RPGs exploding nearby, these men worked to cut the pilot out of his cockpit. It was slow, grueling work. Every minute they worked was another minute we had to hold the line. Another minute exposed.

The sun was fully up now. The shadows were gone. We were naked in the light.

Finally, the word came down. “We got him. We’re moving.”

They pulled Cliff’s body from the wreck. We wrapped him up. We loaded him onto a vehicle.

“Mount up! We are leaving!”

I looked around. The vehicles were packed. The Humvees were full of bullet holes and shattered glass, filled to the brim with the dead and the dying. The APCs were stuffed like sardine cans with the wounded and the assault force.

I ran to the back of a Malaysian APC. “Open up! Let us in!”

A terrified face looked out from the hatch and shook his head. “No room! No room! Full!”

I tried another vehicle. Same thing.

There were too many of us. The relief column had taken casualties on the way in. They had loaded up the wounded from the crash site. There was no space left for the healthy—or the “walking dead,” as we felt.

The convoy commander’s voice crackled over the radio, tight with stress. “We are taking heavy fire. We have to move. We are moving now.”

The engines roared. The tracks churned the bloody dirt. The vehicles began to lurch forward.

“Wait! Wait for us!”

They didn’t wait. They couldn’t. If they stopped, they would die. The RPGs were hammering them. They had to keep momentum.

So, we did the only thing we could do. We tightened our weapon slings. We checked our ammo—most of us were down to our last magazine. We looked at each other.

“We’re walking,” the platoon sergeant said. His voice was flat, void of emotion. “Stay on the sides of the vehicles. Use them as cover. Do not stop.”

This was the Mogadishu Mile.

It wasn’t a mile. It was closer to two or three, depending on the route, but it felt like a marathon run through hell.

We started running.

As we stepped out from the cover of the buildings, the city erupted. The Somalis saw the vehicles leaving and knew the foot soldiers were exposed. The noise was indescribable. It was a solid wall of sound.

I ran alongside a tank, my shoulder brushing against the hot metal tracks. The tank was my shield. On the other side of it, the world was exploding. But the tank was moving fast. Too fast.

“Slow down! Goddammit, slow down!” we screamed.

But the tankers were buttoned up inside. They couldn’t hear us. They were terrified, just trying to get out of the kill zone. The vehicles accelerated, pulling away from us.

Suddenly, our cover was gone.

We were alone in the street. A long, ragged line of Rangers and Delta operators, running in daylight, down the main boulevard of Mogadishu.

The air snapped around me. Snap. Snap. Snap.

I saw bullets striking the pavement at my feet, kicking up little puffs of dust. I saw them hitting the walls next to my head.

I raised my rifle, firing wildly at a window where I saw a muzzle flash. I didn’t even aim. I just wanted to keep their heads down.

“Keep moving! Don’t stop!”

My lungs were burning. My legs felt like they were made of lead. The sweat poured into my eyes, stinging like acid. My gear—the body armor, the helmet, the ammo, the water—weighed a hundred pounds.

I saw a guy go down ahead of me. He didn’t scream. He just crumpled. Two others grabbed him by his vest and dragged him. They didn’t stop running. They just dragged him.

We ran past the wreckage of cars. We ran past burning tires. We ran past the bodies of the militia we had killed. The street was a corridor of death.

I remember looking up at a rooftop and seeing a woman. She wasn’t holding a gun. She was just watching. She looked bored. That image stuck with me. The indifference of it. We were fighting for our lives, and she was just watching the show.

We reached a rally point, hoping to get on the vehicles. They were gone. They had pushed through to the Pakistani Stadium.

“Keep going! To the stadium!”

We ran. We ran until our hearts felt like they were going to burst. We ran until the sound of the gunfire started to fade behind us, replaced by the sound of our own ragged breathing.

And then, we saw it. The stadium.

It was a fortress. Pakistani tanks were guarding the perimeter. UN flags were waving. It looked like the pearly gates.

We stumbled through the entrance. The adrenaline crash hit me the moment I crossed the threshold. My legs gave out. I didn’t fall; I just kind of sank to the ground.

I sat there in the dirt, gasping for air, staring at my boots. They were covered in blood. I didn’t know whose it was. It could have been mine. It could have been Jamie’s. It could have been the guy next to me.

The stadium was a surreal scene. There were hundreds of soldiers from different nations. The Pakistanis and Malaysians were looking at us like we were ghosts. We probably looked like it. We were caked in dust, sweat, and blood. Our eyes were hollow.

“Water,” someone croaked.

They brought us water. It was warm, and it tasted like plastic, but it was the best thing I had ever tasted.

I looked around at the survivors. We didn’t cheer. There were no high-fives. We just sat there, silent. The silence was heavy. It was the silence of men who had seen too much.

Then came the count.

We started hearing the numbers. The cost.

18 dead.

Eighteen.

Cliff Wolcott. Donovan Briley. Ray Frank. Bill Cleveland. Tom Field.

And the operators. Gary Gordon. Randy Shughart. Earl Fillmore.

And the Rangers. Jamie Smith. Casey Joyce. Richard Kowalewski. Dominick Pilla. James Cavaco. James Martin.

Eighteen of the best men I had ever known. Gone. Just like that.

Over 80 of us were wounded. That was more than half the assault force.

And for what?

We sat there in that stadium, and the question hung in the air like smoke. For what?

We had captured the lieutenants. But Aidid was still out there. We had killed over a thousand of his militia , but there were thousands more.

Mike Durant was missing. We knew he was alive, or at least we hoped, but he was in their hands. The thought made me sick.

General Garrison came to see us. He walked among the men. He looked aged, like he had aged twenty years in one night. He took full responsibility. He didn’t blame the pilots. He didn’t blame the intel. He didn’t blame us. He said, “This is on me.”

I respected him for that. But it didn’t bring the boys back.

The days that followed were a blur. We got patched up. We cleaned our weapons. We waited.

Mike Durant was released 11 days later, on October 14th. Seeing him come back was the only victory we really felt.

But the political winds had shifted. The images of our dead brothers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu had hit the TVs back home . The American public, who had been told this was a humanitarian mission, was horrified. They didn’t understand why their sons were dying in a dusty alley in East Africa.

President Clinton ordered a withdrawal. The US forces pulled out in 1994. The UN followed in 1995.

We left.

We packed our gear, loaded the planes, and flew away. We left the anarchy. We left the warlords. We left the starvation.

Aidid, the man we had sacrificed so much to catch? He died three years later. Not by a Delta sniper, not by a Ranger raid. He died of a heart attack after being shot in a fight with a rival clan. . The irony was bitter. The internal chaos of Somalia took him out in the end, something we had tried to force and failed.

His son, Hussein Farrah Aidid—a former US Marine, believe it or not—took over. The cycle continued.

So, was it a failure?

If you look at the history books, if you look at the political objectives, yes. It was a disaster. It was a “debacle.”

But if you ask me? If you ask the guy sitting on this couch thirty years later?

I don’t think about the politics. I don’t think about the UN resolutions.

I think about the guy who ran into the street to drag me to cover. I think about the pilots who flew their helicopters into a wall of lead because they heard us screaming for help. I think about Gordon and Shughart, who looked death in the face and jumped in anyway.

They didn’t fight for a flag. They didn’t fight for a president. They fought for the man next to them.

That’s the secret they don’t tell you in the recruiting commercials. You go to war for your country, but you die for your friends.

The legacy of Black Hawk Down isn’t the movie. It isn’t the book. It isn’t the political fallout.

The legacy is the brotherhood. It’s the bond that was forged in that fire. A bond that can never be broken.

We came home. We got jobs. We raised families. We got old. But a part of us never left that city. A part of us is still running that Mile, lungs burning, heart pounding, waiting for the sun to rise.

We remember them. Every day.

Rangers Lead The Way.

End of Story.